Renewable energy developments continue at break-neck speed, with US$644bn to be spent on new capacity in 2024, but outdated and inadequate power grids could prove to be a significant stumbling block to the energy transition

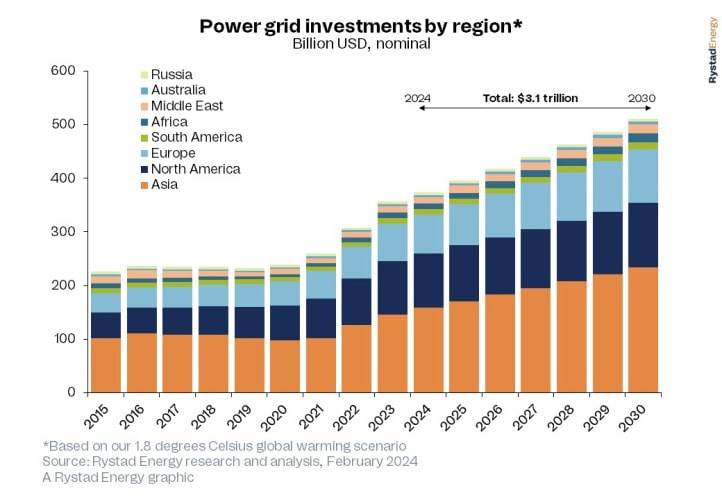

If the world is to limit global warming to 1.8 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, US$3.1tn of grid infrastructure investments are required before 2030, according to Rystad Energy research.

In that scenario, an additional 18 million kilometers of grid network would be needed to keep pace with the electrification underway across cities and counties, including new renewable energy capacity and the rapid adoption of electric vehicles. This would take the total length of all power grids worldwide to 104 million kilometers in 2030, expanding to 140 million kilometers in 2050 – almost the same distance from Earth to the sun. The immediate expansion by 18 million kilometers would necessitate nearly 30 million tonnes of copper, a commodity already in short supply.

Growing global power demand is the main factor driving the need for grid enhancements. This rise is driven by population expansion, industrialisation and urbanisation in developing countries, and efforts to mitigate climate change through electrification. Cybersecurity, geopolitics and the increasing priority for securing reliable national energy supply also contribute to the need. Yet, inefficient regulatory frameworks could significantly delay grid developments and, in turn, the energy transition.

“Power grids will be both an enabler and an obstacle to the energy transition. Mature grids have enabled the rapid expansion in solar and wind capacity seen in recent years, but many national grids are now near or at the point where further connections cannot be made without upgrading or expanding them. Annual investment levels must increase if the current trend of renewable energy buildout is to continue,” commented Edvard Christoffersen, senior analyst at Rystad Energy.

The total combined length of all transmission and distribution networks globally is around 86 million kilometers, a distance long enough to encircle the planet more than 2,100 times. The transmission grid comprises six million kilometers of high-voltage lines (over 70 kilovolts [kV]). In comparison, the much larger distribution grid consists of around 8 million kilometers of medium-voltage (10 to 70 kV) lines and a colossal network of low-voltage (less than 10 kV) lines traversing about 72 million kilometers, reaching households in all corners of the world. The grid length is set to expand to 104 million kilometers by 2030 and 140 million kilometers by 2050. Asia is set to contribute more than half of global additions this decade, with China and India leading the way as the world’s first- and third-largest power consumers.

We predict global grid investments will reach US$374bn this year, with China accounting for about 30% of the total. Asia will lead in grid expansion investments, but other regions are trying to catch up to keep pace with renewable capacity additions. The US Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) includes US$65bn for upgrading and expanding national power infrastructure, while the European Commission launched an Action Plan for Grids in late November 2023, calling for €584 billion (US$626bn) in investment between 2020 and 2030. The Commission and the European Investment Bank (EIB) are also exploring how to streamline financing to support these significant grid investments. In the UK, National Grid launched an action plan to revamp its network for the first time in decades, investing over £16 billion (US$20.16bn) in upgrades between 2022 and 2026.

The rapid expansion of the power grid will require vast volumes of raw materials, especially copper and aluminum. Copper is primarily used as the conductor in underground distribution, transmission and subsea cables, while overhead lines use aluminum. Although aluminum is predominantly used in overhead lines, it can be substituted as a conductor in underground lines. Demand for copper and aluminum is expected to surge by almost 40% by the end of the decade, but grids are not the main driver. They are also vital to myriad other applications within the construction, transportation, renewables and consumer products industries. Grids only account for roughly 14% of copper demand globally, or about 4 million tonnes in 2024.

Lengthening the network is necessary to support intermittent and remote renewable power generation and to connect new industrial, commercial and residential areas, but alternatives to meet growing power demand also exist. Implementation of large-scale battery storage can address intermittency issues associated with renewables and allow for higher average grid loads, reducing the need for new lines. Overhauls and upgrades of the existing grid can increase the capacity per kilometer and digitalisation can free up capacity by solving flexibility issues. At the same time, distributed energy sources such as rooftop solar can reduce the need for new lines. What is clear is that the world’s current grid infrastructure does not meet the demands of the future energy system.

Tortuous permitting processes are already causing bottlenecks in many countries, including the US and the UK. Adopting large-scale battery storage solutions and grid digitalisation can address some grid intensity issues, but the electrification of society will spark greater attention and efforts to streamline regulatory frameworks and encourage investments so grids can be an enhancer rather than an inhibitor of the energy transition.